“This place is not a place of honour... no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here... nothing valued is here.”

Jon Lomberg is a space artist, as well as a science journalist and longtime collaborator of Carl Sagan’s. His work focuses on “projects that involve unusual communication problems”1 and he was one of hundreds of individuals—designers, artists, linguists, geologists, anthropologists, archaeologists, sociologists, psychologists—who were petitioned by the U.S. government in the '90s, to answer an intractable question— a riddle, really: how can we communicate with our descendants across vast periods of time, generations living ten thousand years from now?

The project itself had all the hallmarks of a classic thought experiment, but its objectives were precise, its consequences very real—potentially catastrophic. And its conclusions—or some of them, at least—would be actualised and can be observed today. US federal agencies, universities, national laboratories, corporations, and members of the public also contributed to the study, whose findings were published in November 1993 in the Sandia Report—Expert Judgment on Markers to Deter Inadvertent Human Intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant.

On the 24th of July 1990, a letter was sent by D. Richard Anderson of Sandia Laboratories seeking expert collaborators—Carl Sagan was one of the recipients — for the study. It read: “The safe disposal of nuclear waste is one of the most pressing issues facing the United States today. The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP), located in New Mexico, is to be the first of this nation’s nuclear waste repositories.”

What comes next is more interesting: the nominees were being asked “to participate in the identification of characteristics for selecting markers to be placed at the WIPP site; a marker system that will remain operational during the performance period of the site (10,000 years).”2 The bracketed timeframe is funny to me. It’s as though it’s an aside, merely a detail—rather than the precise reason this interdisciplinary exercise was, and remains, so fascinating. And, more than that, such an onerous problem.

Lomberg was interviewed on the podcast, 99% Invisible—and I recommend listening to it—“I had a moment of wondering if it was a joke,” he says of receiving the Sandia Laboratories letter. “Usually, you don’t get asked to design something that’s going to last ten thousand years; that’s twice the span of recorded human history.”

But the ten-thousand-year timeline was chosen quite arbitrarily, to make the task appear somewhat conceivable; the radioactive waste buried near Carlsbad, New Mexico, would, in fact, be dangerous for much, much longer: hundreds of thousands of years. The assumption was made by those overseeing the project, that it would be humans encountering the site and reading the messages or markers that the committee designed, rather than extra-terrestrials or some other kind of non-human entity.

But even given these parameters, this enterprise represents a stress test for the durability of language, symbols, “markers”; a summary of—even a referendum on—the possibilities, efficacies and limitations of human-to-human communication. Roman Mars and Matthew Kielty, the hosts of 99% Invisible, make some interesting observations themselves. Citing Beowulf, a text written in Old English and dating back to around 975-10253 — at least in manuscript form — they describe it as “basically incomprehensible” to a contemporary reader.

It’s “like a different language… you can recognise most of the letters as being part of the English alphabet, but they barely correspond with how we use those letters today.” But Beowulf is only a thousand years old and since the aim was to devise a way to communicate across ten times that timespan, relying on the survival of any existing language being intelligible to somebody so far in the future seems fanciful at best.

Tamil, often considered the world’s oldest extant language is perhaps 5,000 years old. But it’s generally subdivided into Old, Middle and Modern Tamil and the earliest examples of it in written form date back to around the 5th century BC – and even these examples are disputed.4

The use of the term “markers” in Anderson’s letter in 1990 and the Sandia Report itself might be understood as a pre-emptive attempt to exclude language itself as a medium of communication for this project. Or, perhaps, to reframe language as merely one kind of “marker” among many, along with pictorial depictions, storyboards, symbols.

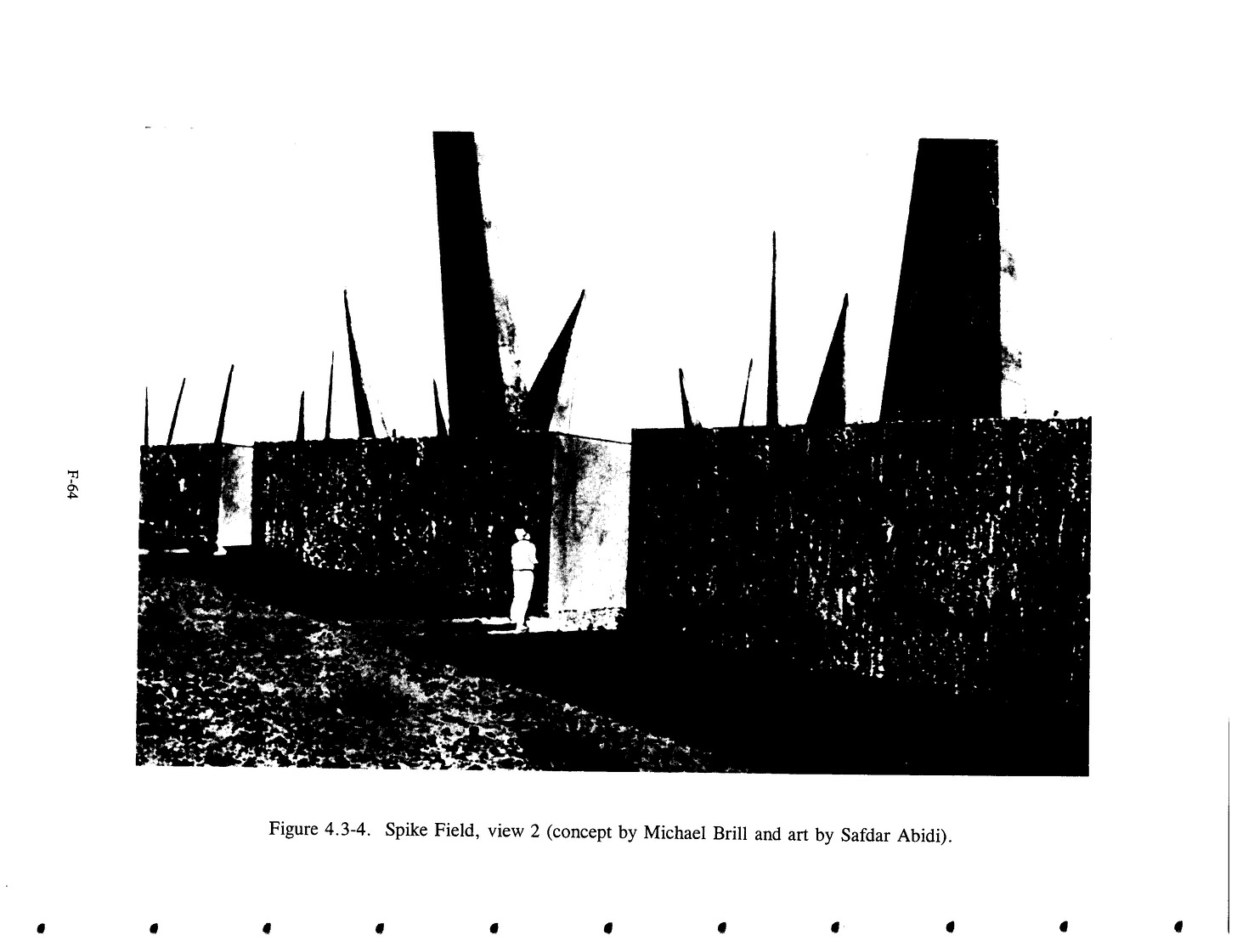

The report even gestures to the design of the site, and the manipulation of the surrounding landscape, as a form of “natural language” to be considered as a possible vehicle for conveying a warning that is both tremendously urgent and that would need to outlast any of the study’s participants by millennia.

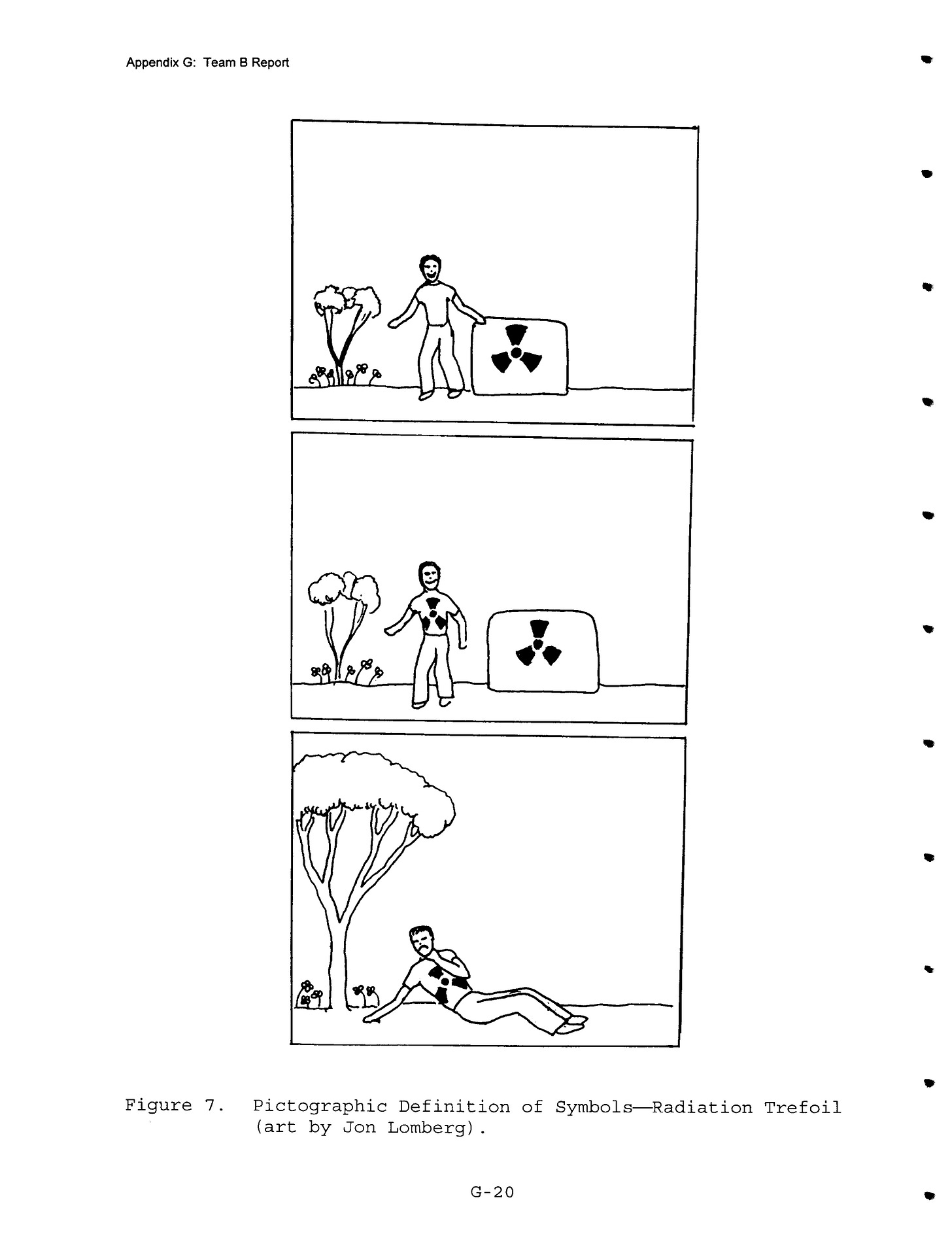

But visual depictions, too, proved problematic. The image below was produced by Lomberg. At first glance, it might seem like it could serve as an effective deterrent in principle (if you ignore the amusingly child-like nature of the drawings) but it only works if we assume that the person encountering this signage is inferring the causal links from top to bottom; interpreted in reverse, it may give the impression that the radioactive waste depicted has healing or even revivifying qualities.

Just as some languages, like Arabic, are read from right-to-left, rather than left-to-right, it seems dangerously presumptuous that this storyboard would be understood in the way its creator intended.

That said, the participants needed to begin with language. At least in order to determine what kinds of messages, exactly, they wanted to communicate. This went beyond simply conveying danger, hazard, or the lethal nature of the site’s contents.

Something quite specific needed to be accounted for, and avoided: as humans, when we discover extremely old structures of any kind—and especially if they have the appearance of being meaningful edifices, monuments, or places of worship—our curiosity is piqued and aroused. We want to know more. We want to know, for example, what’s inside or beneath the Giza Pyramids. What they meant to the civilisation that created them. This instinct is likely immutable and congenital.

While it’s safe to assume that the 120th century would be deeply unfamiliar to us, it’s almost certainly true that if human beings still populate the Earth at that time, their sense of curiosity about the past will be undimmed. It’s against this background that a number of suggestions emerge—that it’s crucial the site is not amenable to the interpretation that it’s sacred:

“In natural language, a vertical stone means: an aspiring connector between us (on earth) and an ideal (up there); that we “stand up” with pride about this honoured phenomenon. The marker is a symbolic inhabitation of the place it occupies.

Its size and workmanship is a sacrifice of much work and resources to a memory. It is a strong suggestion (because we left it to them, and it is of durable material) that future people also give honour to the memorialised phenomenon.

When we use this particular physical form of the vertical marker, both its historic use as an honorific and its meanings in natural language may well send a message that this is an honoured place, a place about a “good” both in our culture and in the culture of future observers.

Such a message would be inappropriate for the WIPP site. This discussion is not meant to discard use of markers, but to re-examine some underlying assumptions and, perhaps, to place markers in the context of a larger set of markings. The team recommends the use of vertical masonry markers, if their form feels dangerous, more like jagged teeth and thorns than ideals embodied.”

Even Carl’s Sagan’s suggestion—while he was not present in New Mexico for the project, he sent a letter outlining his proposal for appropriate “markers”—was contentious: the skull & crossbones. Could we be sure that symbols, even those with centuries-old and potent connotations, would endure?

Historically, the meaning of the skull & crossbones itself isn’t as stable as we might think. Like language, symbols, and what they represent, “can shift over time. The skull and crossbones actually began not as a symbol of death, but a symbol of rebirth. The earliest uses of it are in religious paintings and sculptures from the Middle Ages. At the foot of the cross where Jesus is crucified, there lies a skull with two bones in the shape of a cross, not an ‘x.’ The skull is supposed to be that of Adam.”5

And the skull & crossbones has been commodified and appropriated by popular culture. It’s the symbol of The Brotherhood of Death, an undergraduate senior secret student society at Yale University6. It appears in comic books, on clothing, key-rings and stickers.

An article in Minnesota’s Pioneer Press notes that “bikers in the 1960s and ’70s sported the symbol to identify themselves as anti-establishment. Heavy-metal bands did the same thing in the 1980s, also adding scarves, rings and earrings. Skateboarders followed, then the Goths. As the skull-and-crossbones design became more popular, it lost its edge.”

Kevin Jones, a curator at the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising in Los Angeles, told the reporter “I saw a skull-and-crossbones Hello Kitty,’ Jones said. ‘When you see that, you know it has been totally divested of any of its toxic power. It’s simply become a fun, kitsch symbol.”7 Ultimately, the problem hasn’t been solved and none of the more interesting and inventive proposals have been implemented by US Department of Energy at the WIPP site. For now, at least.

“In 1994, Level II, III, and IV messages in English were translated into French, Spanish, Chinese, Arabic, Russian, and Navajo, with plans to continue testing and revision of the original English text and subsequent eventual translation into further languages.”8

Perhaps technology will step in and solve this problem—the internet and, certainly AI—are much more mature now than they were in the '90s. But it’s clear that these innovations can be used to distort as well as to enlighten, so it seems like the jury’s out when it comes to “long-term nuclear waste warning messages” or “nuclear semiotics” as it’s now referred to.

To my mind, though, the very fact that this colossal, high-stakes investigation into producing messages that will endure for millennia failed makes it all the more fascinating.

https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/ten-thousand-years/

Sandia Report, Expert Judgment on Markers to Deter Inadvertent Human Intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, November 1993

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beowulf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_languages_by_first_written_account

https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/ten-thousand-years/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skull_and_Bones

https://www.twincities.com/2007/05/18/no-bones-about-it-skull-and-crossbones-style-makes-a-killing-in-pop-culture-with-success-of-pirates-of-the-caribbean-series/

https://www.wipp.energy.gov/library/permanentmarkersimplementationplan.pdf

Good read, another interesting book on this general topic is Extra Terrestrial Languages by Daniel Oberhaus—it’s about how we could even message or communicate with ETs as a whole. The book is from MIT Press before anyone screams quack.

omg but one of the most interesting things to come out of this nuclear semiotics mess is the atomic priesthood! i’m surprised it wasn’t mentioned here as an alternative solution haha

here’s a link to the article that proposed it https://www.zygonjournal.org/article/id/14327/

alternatively i’ve also found myself going down the same rabbit hole about the ephemerality of language and have a post on here titled “isopods & the atomic priesthood” if you’d like to check it out :’)