“I’ve often wondered what drove the man, what animated him, as you say.

Thoughts of ‘what if it had happened to our children? What if it had been our children that had been murdered? What if it was his art, his window, that had been smashed by the explosion?’

He would obviously have felt a link, a connection, with the people of Birmingham.

Behind the horror of that Sunday morning, deeper than a knee-jerk reaction to the awful news, what was going on in John’s head?

Did he still have images of war in his head? Perhaps, for him, the war was still going on.”

These are the words of Andy Edwards, founding member of the wonderfully named Carmarthen quartet, The Water Poets.

Andy is a musician and storyteller whose work is really a mission. “Make It Right”—a musical project inspired by the Welsh response to the violence and racism that blighted and scarred Alabama in the '6os—is currently his principal preoccupation.

“‘MAKE IT RIGHT’ is a suite of songs, a cross genre mix of gospel, blues, jazz and folk that responds directly to the racially motivated terrorist attack on September 15th, 1963, with a Welsh perspective. Wales reacted, as a nation, and responded in a way that we must be proud of 60 years later.

Social history crumbles, fades into obscurity, unless the next generation fight to keep it alive. The story of the Wales Window of Alabama needs to be kept in the consciousness of the Welsh public. The artistic response of John Petts to the atrocity directly links the Civil Rights Movement with Wales. This is the inspiration for our work.”

As well as performing a potent blend of gospel, blues, jazz, and folk music, he visits primary and secondary schools across Wales, telling the story of The Welsh Window of Alabama to younger generations—the project is an exercise in storytelling and historical preservation.

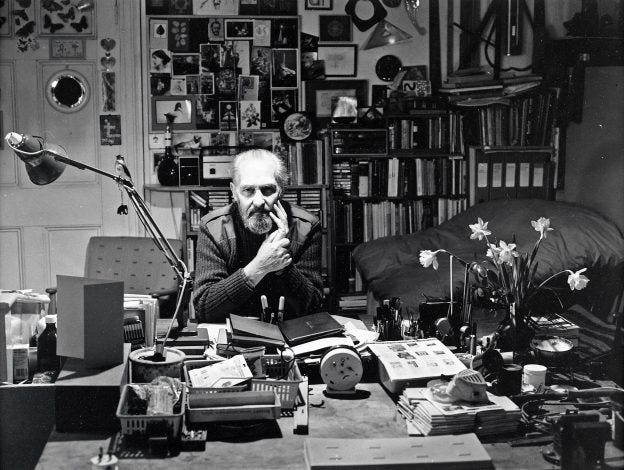

The reason for our correspondence is our mutual interest in this story—though I heard about it quite recently; while Andy has known the history for years—and the unlikely cultural link between Wales and Alabama that’s endured over the last sixty years. And, of course, we share a fascination with the man who created this piece of art, this artefact: John Petts. And why, exactly, he responded the way he did to a terrible news story he heard about on the radio one Sunday morning in 1963. A racist terrorist attack that had taken place over 4,000 miles away.

Sixty years ago, on the 15th of September 1963, the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama—perpetrated by four members of the Ku Klux Klan—left four Black girls dead and the church itself decimated. Nineteen sticks of dynamite had been rigged in the church that morning and the ensuing explosion “blew plaster off the walls and peeled the face off the image of Jesus in a stained-glass window.”1

Martin Luther King had delivered his indelible “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. barely two weeks before the attack.

“As the bricks and mortar caved in the interior wall and smoke filled the building, most of the worshipers were able to escape.

However, the bodies of four little girls were found beneath all of the rubble. Cynthia Wesley, 14, Carole Robertson, 14, Addie Mae Collin, 14, and Denise McNair, 11, were discovered in the basement restroom.

Sarah Collins, 10, was also in the restroom during the explosion and lost her right eye. The girls had been at church for Sunday school, where the day’s lesson was ‘A Love That Forgives.’ More than 20 other people were injured.”2

During the protests that followed, another two black children were shot and killed by police: 13-year-old Virgil Ware and Johnnie Robinson, 16.

At the time, Alabama was the most racially segregated state in the US. As Adam Fairclough describes in his comprehensive history of the battle for civil rights, Better Day Coming: Blacks and Equality:

“Everyone knew that Birmingham was a powder keg. A Klan stronghold, it had experienced so many explosions – about fifty since 1947 – that local blacks dubbed it ‘Bombingham’. Targets included the homes of black people who had moved into white neighbourhoods, the homes of civil rights activists, and Bethel Baptist Church. The police seemed incapable of apprehending the perpetrators: many policemen sympathised with the Klan and some belonged to it”.

Petts had served in the Second World War as a medic and had witnessed the horrors of war personally: in the Ardennes, then crossing the Rhine and travelling north to the Belsen concentration camp. And most harrowing of all, he’d been captured and detained: he’d been a prisoner of war.

While Petts died in 1991, a series of interviews he gave have been preserved by The Imperial War Museum, which convey his visceral reaction to the news from Alabama. And there are echoes of what Andy suggested to me in Petts’ own words: “naturally, as a father, I was horrified by the death of the children. As a craftsman… I was horrified at the smashing of all those windows, and I thought to myself: my word, what can we do about this?”3

We know what he did next. Petts enlisted the help of The Western Mail and its readership—and together they established a fundraising campaign to aid the traumatised congregation of the 16th Street Baptist Church, as well as the broader community. The very next day, The Western Mail led with the rallying imperative: “Alabama: Chance for Wales to Show the Way.”

With over three thousand donations, each amounting to no more than half a crown (about £1.50 in today’s currency)—a maximum sum that Petts had stipulated, in order for the project to represent a gift from the Welsh people as a whole, rather than a select few benefactors—the fundraising target of £500 was soon met and exceeded. Almost double that amount—£900—had been received by the time the fund was closed.

What’s most remarkable to me about the seldom understood relationship between Wales and Alabama is its durability; particularly since—according to Petts—the residents of Birmingham “had never heard of Wales, had no idea where it was”. When it was shipped across the Atlantic in 1965, finally arriving in Mobile—a port city on the Alabama coast—Andy tells me that “the stevedores and truck drivers that handled the window needed to be Black” so that Klan members, or anybody else who might confiscate the panel, could be eluded.

The stained-glass window remains, intact, at the 16th Street Baptist Church and “has become an important historical landmark, attracting thousands of visitors each year. The window is regarded as one of the key icons of the American Civil Rights Movement—a powerful protest against intolerance and injustice. It’s the most celebrated international example of Petts’ work and is believed to be among the first depictions of Christ as a Black man in this medium.4

Only last month, the Welsh government published a press release, reaffirming the country’s links to the US state—and Vaughan Gething, Minister for the Economy, addressed the 16th Street Baptist Church Commemoration on the 15th of September, “alongside the first black woman US Supreme Court Justice, Ketanji Brown Jackson.”5

And the relationship is reciprocal. In June of this year, the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s gospel choir, led by Dr Reginald Jackson, arrived in Wales to commemorate this historic relationship that dates back decades—marking a pivotal anniversary in the American civil rights movement.

The choir embarked on a tour of South and West Wales, performing in Cardiff and Aberystwyth University. They were also a highlight at the Urdd Eisteddfod, an annual celebration of Welsh culture, in Llandovery. Jackson told the BBC: “we learnt some gospel music in Welsh. We struggled with the language because it's so different from ours. But we did it. It was special for us.” He went on to describe his choir’s performance at the Urdd Eisteddfod as “life changing, just to see the depth and breadth of the culture."6

I think it’s appropriate for Petts himself to have the last word on this extraordinary story—one that feels so contingent, so reliant on the man himself—and yet has had such a profound impact. One which reverberates still, to this day.

In a 1987 interview with the BBC, he insisted that:

"An idea doesn't exist unless you do something about it. Thought has no real living meaning unless it's followed by action of some kind."

www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/09/15/birmingham-church-bombing-60-years/

web.archive.org/web/20170813104615/http://ajccenter.wfu.edu/2013/09/15/tih-1963-16th-street-baptist-church/

www.walesartsreview.org/against-the-evil-of-violence-the-wales-window-of-alabama/

c20society.org.uk/news/the-guernica-of-brighton-listing-bid-to-save-modernist-synagogue-and-holocaust-memorial-windows

www.gov.wales/welsh-government-marks-60th-anniversary-16th-street-baptist-church-bombing-and-reaffirms-historic

www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/american-gospel-choir-historic-link-27064877

I really enjoyed reading this Stefan, a truly moving story. It makes me proud of our welsh roots...

I loved the photos too and Petts quote at the end. So true.