Drag—as performance, a form of self-expression, even as art—is something I love and take great pleasure in. From John Waters’ films with Divine—I finally watched Pink Flamingos with my mother last Christmas (quintessential festive viewing)—to the absurdist, hilariously morbid sketches in The Divine David Presents; Leigh Bowery’s extraordinary, ornate costumes; the tender, affecting documentary-tribute to the ballroom scene of New York in the 1980s, Paris Is Burning; the musical and film Hedwig & The Angry Inch.

All these depictions and interpretations that exist under the penumbra of “drag” mean a lot to me. I’ve never wanted to be a direct participant myself but, as a cultural phenomenon, drag feels like an integral part of the gay world. A subculture and shibboleth, something that’s ours.

Whether you actually enjoy drag yourself isn’t really the point. I do and so do many other gay men—and plenty of women, too—but I know quite a few who don’t. Regardless, it’s both an indispensable part of gay history and the contemporary LGBT scene.

I was a teenage goth—face daubed with kohl, my chest and arms layered in torn fishnet tights—less a nod to the aesthetic of Placebo’s Brian Molko than outright sartorial theft. This had something to do with gender expression, I suppose, but I’m not sure I saw it that way at the time. Certainly, though, it had something to do with me being gay and “alternative”. At a stretch, you could call this drag – but I wouldn’t label it like that myself.

Now, though, drag is emphatically mainstream. Thanks, really, to one man in particular: RuPaul Charles. His TV franchise-juggernaut, RuPaul’s Drag Race, hurled drag into—and at—polite society in 2009, before becoming so ubiquitous and rote that a sense of fatigue is notable even among its most ardent fans (myself included).

I still enjoy the UK version; the fifth series looks due to land on our screens fairly soon and there’s no doubt I’ll be watching.

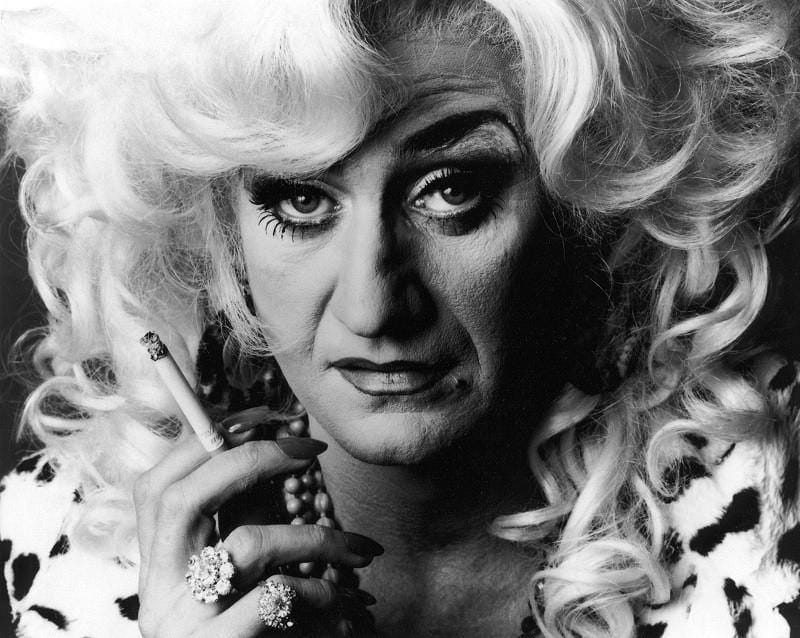

Of course, we had Lily Savage, the creation of the late Paul O’Grady in the '90s (though he began performing as Savage in the '70s at the Black Cap in Camden and then The Royal Vauxhall Tavern—an incubator for so many drag performers)— and I remember her well. But he retired the act in the 2000s, telling The Mirror in 2021 that his drag persona wouldn’t be tolerated in the more censorious cultural environment we live in nowadays1.

On whether he would consider returning to the stage as Lily Savage, he had this to say:

“Good God no, I wouldn’t last five minutes. It’s just the things that she comes out with. It’s a different time now. They probably wouldn’t like the inference that she was a lady of the night — she’d have to say she was a sex worker or just, ‘Worked in hospitality”.

It’s funny, then, that many of the contestants on Drag Race are far more louche, risqué – outrageous – than Lily Savage ever was.

But this trajectory: the commercialisation and increasing visibility of what’s historically been a form of entertainment consumed by gay people (and gay men in particular) has been met with considerable backlash—some of it as venomous as it is dubious.

A great deal of this “criticism” amounts to straightforward homophobia. Confected outrage at children being exposed to drag queens in libraries (the horror!); the grotesque insinuation that drag is a vehicle for grooming; the tedious, ultra-conservative fulmination that “men are no longer men”—that we are being emasculated by a culture that deems the male sex intrinsically toxic.

Criticism of this kind is offensive, but it’s also fairly easy to dismiss as the bigotry it is. The problem, though, is that critiques of drag actually come from a plurality of perspectives and—more often than not—all criticism of drag is regarded as unvariegated and born of prejudice.

A particularly intransigent form of cultural conservatism still exists. It rails against modernity, the sexual revolution and gay marriage—and cleaves to mid-twentieth-century conceptions of gender roles, while indulging in an intoxicating tincture of nostalgia and prejudice—and regards drag with the disgust and contempt you’d expect it to.

Given that such patent homophobia is the driving force behind so much of the condemnation of drag renders its supporters and fans (not to mention its performers) extremely defensive—and for understandable reasons.

But, to my mind, this instinct to defend drag—because it is a proxy for gay rights and liberation—blinds some commentators and individuals to some of its more reasoned and cogent appraisals. I’m thinking specifically about feminist critiques.

So this is where we find ourselves: feminists who argue that male drag performers often at least appear to parody or mock women, are often regarded as de facto indistinguishable from reactionary conservatives (particularly in the US, but increasingly here in the UK, too) who disdain it as debauched and adjacent to pederasty.

Julie Bindel recently wrote a piece in The Spectator in which she outlined her views on drag queens—and while I disagree with most of its content—it’s clearly a critique that’s couched in the former category2.

Bindel, challenging the BBC’s decision to include the drag queen Cheryl Hole—whose real name is Luke Underwood-Bleach—on the TV show on Celebrity Masterchef, put it like this:

Let him [Underwood-Bleach] present the hosts with as many pound shop plates of nosh as he can possibly manage, but will the BBC put a curb on any sexist behaviour? If he parades around the studio perpetuating harmful and offensive stereotypes about women, will this be dealt with?

Women already have enough misogyny to contend with, and that’s exactly what I consider Underwood-Bleach’s performances to be. It is not a sign of affection when men decide that they are going to parody their own fantasy of ‘working class slags’ – which is the blueprint used for the majority of drag characters. They are having a laugh at our expense, and it is far from harmless fun.

It’s worth noting here that Cheryl Hole, in and out of drag, speaks and behaves in a very similar way. Sure, when he’s performing as his drag persona, he exaggerates many of his mannerisms and witticisms, but – even when presenting as a man – he’s very camp and has a strong Essex accent.

It’s not quite true to say that he “transforms” into a sexist parody once he’s on stage; all the rudiments of his act are quite conspicuous without the clothing, makeup and wigs he dons to become Cheryl Hole, the drag queen. The performer and entertainer.

Besides, the idea that “working class slags” represent “the blueprint used for the majority of drag characters” is an extremely outdated assessment of what drag looks like in 2023.

That said, the reactions that Bindel’s comments provoked across social media were profoundly unnuanced (to the surprise of precisely nobody)—and they were read as homophobic by her critics, to the extent that her piece was read at all. Incidentally, I don’t think the article itself exhibited much nuance either, but even the fact that Bindel herself is a lesbian barely registered, or was glibly dismissed.

I think feminist analyses of drag should be taken seriously—in a way that their conservative, and demonstrably homophobic, counterparts shouldn’t—whether we end up agreeing with them or not.

First off, it’s often claimed that drag is always sexual (or sexualised) and therefore contributes to the objectification of women that permeates society and culture so deeply. But that’s simply not true—or, at least, it’s only partially true. Even on Drag Race, you’re just as likely to see a performer dressed as some kind of chimera, an extra-terrestrial—something entirely non-human—as you are to see a man depicting a hyper-feminine model torn from the pages of Vogue.

Sometimes, this latter version of drag is overtly sexual, but often the performer is simply emulating or “channelling” a female pop star or celebrity—or expressing their femininity by toying with gender and co-opting the beautiful clothes, accessories, and hairstyles they were so drawn to as gay children and adolescents. Ultimately, I find it hard to see the harm in this. Another relatively common trope draws an equivalence between drag and blackface or minstrelry3. Just as the latter degraded and ridiculed black people, the former does the same for women. While women may not be a minority, sexism and misogyny obviously exist, just as racism does.

But that comparison is both heavily freighted and fundamentally misguided. It’s perfectly reasonable to express a discomfort with drag performers, or to claim that their personas and acts are offensive and reduce the concept of womanhood to an aesthetic. Crucially, though, most drag queens themselves would claim that their acts – while they’re obviously exaggerated, often absurd, and sometimes even intentionally disturbing – are motivated by a desire to celebrate femininity. Often specific women who’ve been adopted as gay icons (Cher, of course, Janet Jackson, Dolly Parton, Joan Rivers, Judge Judy, even—ironically—Margaret Thatcher.)4

The same clearly cannot be said of blackface; nobody would claim that the performers in minstrel shows were paying homage to black people. To try to mount such a defence would be so absurd that nobody would even be tempted to consider its merits. It felt like mockery, degradation and humiliation because it was intended as just that.

So while I understand—to some extent—why some people might be tempted to draw that comparison, I think it’s irredeemably fallacious: not only myopic and deeply insensitive, but also strategically misguided. There are some phenomena and historical episodes we should avoid deploying as reference points because they muddy the waters and discourage conversation by alienating those you’re trying to persuade.

A defence of drag that’s often marshalled is that it’s performed—for the most part—by gay men, who are themselves a minority and vulnerable to homophobia; and that drag is really an homage or celebration of womanhood, rather than an exercise in ridicule, degradation, and mockery. There’s clearly some truth to that and watching an episode of Drag Race and concluding that the contestants’ intentions are even remotely comparable to those who organised or performed in minstrel shows would be preposterous. That said, while the analogy between drag and blackface is deeply unsound, I think we can nevertheless at least comprehend the point it’s getting at.

Speaking to a close female friend, a big fan of drag herself, she pointed to the usage of the words “fish” or “fishy”, meaning a male drag performer who closely resembles a biological woman—or rather, a very particular, extremely feminine, flawlessly made-up, exquisitely dressed depiction of a woman that you might find in a fashion magazine.

I feel uncomfortable when I hear this slang deployed myself. A scenario in which a group of gay men—I’m thinking particularly of Drag Race here—use language that blithely signals their sexual disgust with the female anatomy while dressing as outrageously exaggerated caricatures of women is pretty bizarre.

To be fair, I think terms like “fishy”, however troubling their origins, are part of a gay argot and I don’t think it’s fair to claim that they’re always intentionally misogynistic. But nor does that mean they shouldn’t or can’t be criticised.

My friend also mentioned feeling affronted when depictions of menstruation, pregnancy or childbirth are incorporated into a drag performance—often as the butt of a joke. It’s not hard to see how a man appropriating a uniquely female (rather than feminine), often painful and deeply personal experience—for sheer entertainment—would be disturbing to women.

In these instances, drag performers aren’t simply riffing on female stereotypes or “playing with gender.” They are referencing, or depicting, facts of female biology for the sake of amusement, or even shock-value.

For many women, I can see how this crosses a line from playful to derogatory; from mocking gender roles that women themselves may find ridiculous and restrictive, to reducing women to their biological characteristics and experiences—experiences that are essential to them and that they do not choose to have thrust on them.

This is hardly an exhaustive account of drag and the various critiques that have been meted out against it. But I think it’s important to remember, as gay men who love drag, that not all discomfort with the tropes and paraphernalia of one of our most cherished forms of entertainment—more than that, a key aspect of gay self expression—should be dismissed out of hand.

Many women enjoy drag, too. Others deplore it. And I think it’s worth listening to why that might be. I’ll give Bindel the final word on this. Not because I think her views are beyond reproach but because I think we should engage with what she, and many other women, are saying.

I am so sick of misogyny in the form of drag being treated as though it’s just family entertainment. The fact that the BBC has responded to criticism from feminists with ‘LGBTQ+ representation is important’ confirms for me that they have no idea what such representation should be. This is about women being misrepresented. Women have a right to criticise it, and men have no right to defend it, let alone perform it.”

Mirror.co.uk/3am/celebrity-news/paul-ogrady-moved-on-drag-29577239

Spectator.co.uk/article/why-is-cheryl-hole-on-masterchef/

Slate.com/human-interest/2015/02/is-mary-cheney-right-about-drag-being-like-blackface.html

To be clear, I am not claiming that Margaret Thatcher is widely considered a gay icon – for obvious reasons. But she was definitely very camp, to my mind at least.

I really enjoyed reading this. Plenty of food for thought.

There was a season of drag race where a female drag artist performed. She called out some of the disrespectful language that’s commonplace within the scene (fishy in particular). The drag queen who used the term had never really considered how harmful that could be for a woman. I think it’s important that there are pauses for reflection about feminist critiques around language used.

I love watching drag and for the most part feel it is a celebration of my womanhood.

The fact that drag is changing and so many drag queens identify as women, gender queer and non binary is and will have huge knock on effects on how the craft expresses gender.

I think it’s also interesting to note how many drag queens are politically invested in the rights of women. I was heartened to see the support of the drag community when Roe vs Wade was overturned last year. The main sentiments were 1) we understand the political attack on our bodies.

2) if we are going to dress as women, we need to also support them in their time of need.

It’s easy to point out where feminists and drag queens find points of contention but arguably more meaningful to understand where they politically align.

One thing I would say regarding Story Hours in libraries/schools etc. is that the guy behind Drag Queen Story Hour UK, Sab Samuel AKA "Aida H Dee", ran a crowdfunder for a convicted paedophile's funeral: https://reduxx.info/rest-in-power-drag-queen-story-hour-uk-founder-fundraising-for-convicted-child-sex-offenders-funeral/

Is this representative of drag queens in general? Absolutely no way. But it's a huge red flag and gives lots of fuel to anyone (particularly those you mention on the right) who has concerns about DQSH. Another drag queen in Wales, the organizer of Welshpool Pride, was recently also jailed for child sex offences: https://reduxx.info/uk-drag-queen-who-was-set-to-host-welshpools-first-pride-parade-arrested-during-predator-sting/

I absolutely love Lily Savage, Conchita Wurst, Verka Serduchka, Stanley Baxter, Danny Larue, all that sort of old-school drag. To me, drag queens have to have a talent (typically stand-up comedy or singing) that they're good at - just dressing drag itself isn't enough. Paul O'Grady was a genius comedian, Tom Neuwirth is a powerful vocalist. I think this is where Drag Race goes wrong, because this isn't where its focus lies. I'd recommend Sheluyang Peng's article on how drag stopped being counterculture and what it lost in the process: https://www.societystandpoint.com/p/drag-queen-boring-hour