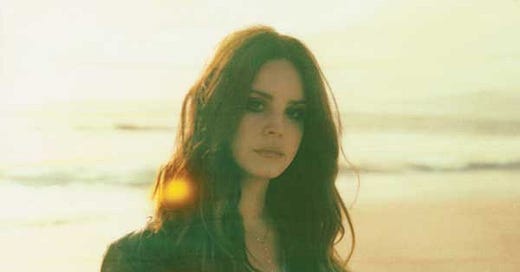

Lana Del Rey is an artist who confounds and puzzles me. She’s often described as “enigmatic”, which is roughly apt but insufficient. I’d add to that: inscrutable and somewhat maladroit (in terms of her relationship with the media, at least). But my confusion is more focused on whether or not I take her seriously. And whether or not I’m supposed to. Does her work have the profundity and depth that I associate with other musicians – or writers or filmmakers – whom I truly respect and admire, rather than merely enjoy?

Also: is she funny?

I recently wrote about how much I love pop music and have grown to respect it. But let’s not pretend that Britney Spears and Joni Mitchell are equals; nor that the former is aiming for what the latter has accomplished. The comparison itself is a category error.

Lana is not my favourite singer or songwriter, but she elicits in me a certain feeling that’s quite unlike my response to any of her contemporaries. And I think that’s because she’s the best example of a pop-adjacent artist whose career is built on a “vibe.” It’s utterly foundational to her career – and, I’d argue, it’s the principal quality that appeals to her fanbase and repels her detractors.

This is not to discredit her songwriting or vocal ability at all; in fact, while I want to make the case for Lana Del Rey being a genuinely brilliant artist – though hardly a consistent one – I also want to mount a partial defence of the word “vibe” and what it connotes.

So here I am – humbly! – writing something dangerously close to music criticism (which I’m altogether unqualified to do) and attempting to redeem a word – “vibe” – from ridicule, disparagement and perceived vapidity.

All that said, Lana has produced more than a handful of songs that I consider pretty much perfect, as well as a couple of albums I would defend as almost-masterpieces, both in the latter half of her career so far: Norman Fucking Rockwell! (2019) and Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd. (2023.)

(Curiously, the former comes with an exclamation mark which isn’t strictly necessary – although I think it definitely adds to the title; and the latter omits a question mark – which renders a sentence that’s obviously a question no longer a question. Odd.)

There’s also Chemtrails Over The Country Club – which I like a bit less – but which boasts the best title, I think, of any recent album I can think of. The sheer economy of those five words together is amazing to me. They capture a sort of atmosphere or moment in culture so succinctly. I simultaneously feel like I know exactly what she’s referring to and that I have no idea at all.

It’s a phrase – a snippet of poetry – that conjures something that’s at once quite specific and totally nebulous. A conspiracy theory located in (or above) an anachronistic milieu, synonymous with a hawkishly guarded American, WASP-ish privilege.

Again, inscrutable, but beautiful; concise but without any obvious meaning.

The name of that album – and what it gestures at, rather than the songs it contains – is a sort of a surrogate or signifier for how I feel about her as a singer-songwriter, persona and pop star. (Although I’m not sure she is a pop star, really.)

She’s someone who very clearly has a persona and an instinct for irony. And yet she denies both these things.

Her real name is Elizabeth Grant – this is not the same as David Jones using the stage name David Bowie, or even Robert Zimmerman going by Bob Dylan. This is Ziggy Stardust territory, or at least close to that.

Is she intentionally misleading the media and her audience? For the record, I don’t mind if she is – I suppose it all plays into that inscrutability. But she doesn’t strike me as calculating exactly; she’s often clumsy in interviews and has a track record of failing to “read the room.”

I tend to think there is an element of conscious misdirection to Lana’s music and presentation. The astounding, bifurcated track “A&W” (read: “American Whore”) precedes a field-recording of a feverish, ecstatic and unsettling preacher. It serves as an interlude on her most recent release.

It’s a clearly intentional juxtaposition:

I mean, look at my hair

Look at the length of it and the shape of my body

If I told you that I was raped

Do you really think that anybody would think I didn't ask for it?

I didn't ask for it

I won't testify, I already fucked up my story

On top of this, so many other things you can't believe

Did you know a singer can still be

Lookin' like a side piece at thirty-three?

God's a charlatan, don't look back, babe

This is obviously incredibly dark and functions as a response to a common refrain from her critics: namely, that she romanticises or glamorises violent interactions and relationships with men.

Take “Ultraviolence”, from the album of the same name, in which she interpolates the lyric “he hit me and it felt like a kiss” from a 1962 song by The Crystals (co-written by Carol King of Tapestry fame). Is her use of this line tantamount to her condoning violence and masochism? Some people seem to think so. Or at least designate it “problematic”. But I think you have to be quite literal-minded to really think this.

The segue from “A&W” to “Judah Smith Interlude” is funny – you can even hear her laughing in the recording – but it’s also jarring and intentionally so. That said, it isn’t merely a joke: the interlude ends with Smith sounding exhausted reflecting that, “I used to think my preaching was mostly about you – and you’re not gonna like this but I’m gonna tell you the truth. I’ve discovered my preaching is mostly about me”.

Why does it end there? To me this seems like a clever piece of ventriloquy.

I remember hearing “Video Games” for the first time – it was the Summer of 2011 and I was sitting alone on Telegraph Hill in New Cross reading some kind of weekend newspaper supplement. I was rapt, immediately.

This debut simply arrived, seemingly out of nowhere, and it’s a perfect song. The languor and romance it evokes from a quotidian little vignette and – on paper at least – pretty unremarkable lyrics, lend it an air of pathos and bathos simultaneously. But the melody is gorgeous and her vocal performance is enormously arresting precisely because of its affected ennui, verging on boredom.

Sounding a bit bored is a key theme for Lana – or, to put it in more generous terms, detached – at once ironic and extremely sincere. It’s a very odd, destabilising experience for the listener and it’s not limited to that song; “Video Games” is simply where it’s encapsulated most clearly and neatly and it’s our introduction to her (as Lana Del Rey, at least).

I think it’s also worth noting the context of popular music from which she and “Video Games” emerged. “Teenage Dream” by Katy Perry had come out shortly before and I think it serves as an instructive contrast. It helps define a shift in pop music that took place around 2011 – and one that Lana contributed to heavily.

Alyssa Rosenberg wrote a short piece in The Atlantic at the time titled “Katy Perry's Teenage Dream Isn't Mine”, in which she’s extremely disparaging about the lyrics:

You think I'm pretty

Without any makeup on

You think I'm funny

When I tell the punchline wrong

Rosenberg writes that “the whole, ‘you're cute even though you're dumb’ thing feels a little gross… it's a sour little line that curdles the fantasy.”

“Teenage Dream” is a fantastic pop song. But Katy Perry represents a kind of pop star that was hugely successful around the late 2000s and early 2010s and yet has no discernible personality, no ambition beyond creating chart-topping bangers. And absolutely no edge at all.

Lady Gaga, who was at the zenith of her career at that time too (and who I have a lot more respect for as an artist than Perry) is undeniably talented: a really great singer, a decent pianist and accomplished songwriter and who certainly had – and has – some kind of edge.

I think Lana actually has changed pop music to some extent – though by no means single-handedly. Lorde and Billie Eilish certainly take after her, as do innumerable pop-adjacent female singers who lean into fragility, darkness and complexity rather than empowerment and platitudinous self-love. (Plenty of room for the latter, I hasten to add).

But Lana still remains a riddle.

How can an artist I admire write (never mind actually release) a song as vapid as “Beautiful People, Beautiful Problems” – featuring Stevie Nicks! – and a song like “The Greatest”, often considered her best song to date.

Focusing on lyrics again, the former offers the listener this risible collection of words:

We get so tired, and we complain

'Bout how it's hard to live

It's more than just a video game

But we're just beautiful people with beautiful problems, yeah

Beautiful problems, God knows we've got them

But we gotta try (la, la, la)

Every day and night (la, la, la)

Or, there’s the song “Beautiful” – brace yourself – which contains this line: “what if someone had asked / Picasso not to be sad?”, followed by a chorus in which she simply repeats the word “beautiful” a total of six times.

But then we have songs like the title track from Norman Fucking Rockwell!:

Godamn, man-child

You fucked me so good that I almost said, "I love you"

You're fun and you're wild

But you don't know the half of the shit that you put me through

Your poetry's bad and you blame the news

But I can't change that and I can't change your mood

Or perhaps even better – and certainly funnier – from “Sweet Carolina” (Blue Banisters):

You named your babe Lilac Heaven

After your iPhone eleven

‘Crypto forever’, screams your stupid boyfriend

Fuck you, Kevin

How is it possible for all these lyrics to come from the same mind? Sentences and lines that range from almost unforgivable vacuity to witty take-downs and deeply thoughtful observations and expression. From total banality to incredibly striking imagery and wordplay?

It comes down to Lana’s all-encompassing vibe: to her fans, these details don’t matter. Or at least not as much as the feelings she evokes and the mood she provides. Her total commitment to her shtick – and I genuinely don’t know if it’s as intentional as it seems – is what carries her through and absolves her of every criminally awful song she’s released (and there aren’t that many).

And when it works, it really, really works.