At thirty-five, I’m not quite a member of the generation that grew up entirely engulfed by the internet. At least not what it’s become since, say, the early 2010s. But I had MySpace when I was in sixth form—and MSN Messenger before that, around the turn of the millennium—until I was taken to one side by a girl at my school, who was much more popular than I was (not that I was much competition in that respect) and told that MySpace was “a bit embarrassing” now. She gently advised me to set up a Facebook account; but I took this as a social edict rather than a mere suggestion. That’s what was cool then. I suppose this was about 2005.

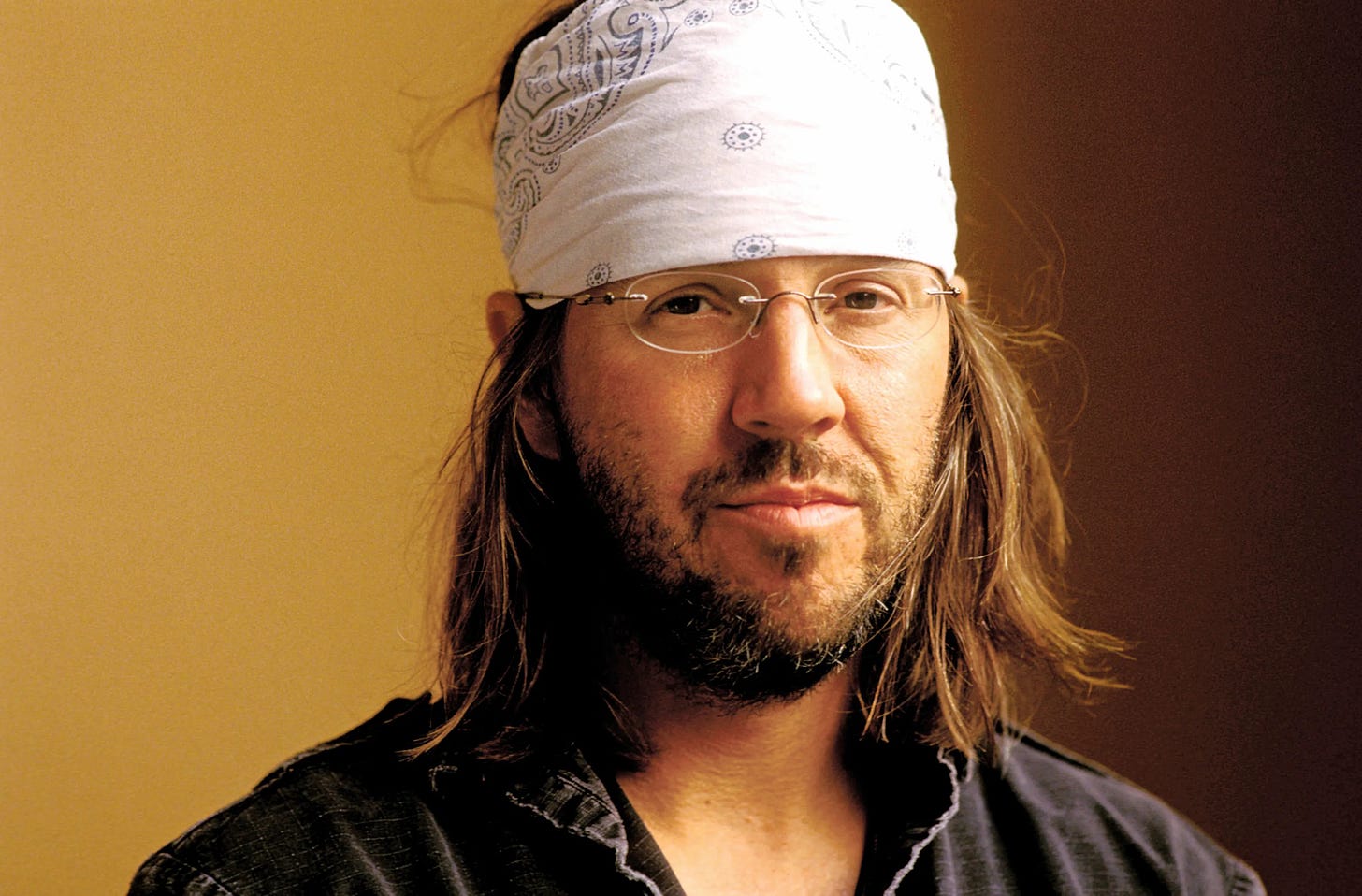

But I’ve been thinking about what my generation—and certainly those younger than me—may have missed out on by being so umbilically tied to online culture and all that comes with it. I’m currently reading Sarah Ditum’s recently published Toxic: Women, Fame and the Noughties and revisiting some of David Foster Wallace’s essays from his 1997 collection, A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again.

Wallace wrote and spoke about television, mass entertainment and the nascent internet with a mixture of soporific circumspection and fondness, even obsession. He went so far as to banish his own TV from his home because he worried that he’d become addicted to it. And he expressed profound concerns about its artifice and what that artifice was doing to us in the '90s.

In one of his most celebrated essays, E Unibus Pluram, he introduces us to Joe Briefcase, our “everyman” and a stand in for the average American who watches, he tells us, on average, six hours of television a day. Joe Briefcase is an invention but the stats around TV consumption are not.

The “great-seeming thing is that television looks to be an absolute godsend for a human subspecies that loves to watch people but hates to be watched itself. For the television screen affords access only one-way”, Wallace writes.

It’s not much of a stretch to apply this analysis of TV to the internet; they serve many of the same functions and supply us with something similar. But it’s true that the internet, especially in 2023, is a much more complex, fractured, and atomised cultural artefact—or place— than TV was in the '90s, or even now.

That said, it’s also obvious that the internet hasn’t replaced TV but subsumed it. It’s cannibalised almost everything. Or you could use the word “incorporated” if you’re feeling less jaded than I am, right now, at the time of writing this.

Wallace continues:

“I happen to believe this is why television also appeals so much to lonely people. To voluntary shut-ins. Every lonely human I know watches way more than the average US six hours a day… lonely people tend to be lonely because they decline to bear the psychic costs of being around other humans. They are allergic to people. People affect them too strongly.

Let’s call the average US lonely person Joe Briefcase. Joe Briefcase fears and loathes the strain of the special self-consciousness which seems to afflict him only when other real human beings are around, staring, their human sense-antennae abristle. Joe B. fears how he might appear, come across, to watchers. He chooses to sit out the enormously stressful US game of appearance poker.”

The pathos in this piece is almost unbearable. And knowing a bit about his life—he spent a month in a psychiatric ward in 1989, where he was treated for alcoholism and told that he’d be dead by thirty if he didn’t stop drinking—makes it hard to believe he isn’t writing, at least in part, about himself.

But there’s levity, too: Wallace was undeniably funny and playful in much of his work. And I don’t want to dwell on the darker aspects of his personal life, which have been well-documented, particularly by his biographer D. T. Max.

So why do we watch TV? And, more specifically, why do we find comfort in “vulgar, prurient, dumb stuff” which hardly even pretends to be anything more than just that?

Wallace offers some analogies: “television resembles certain other things one might call Special Treats (e.g. candy, liquor), i.e. treats that are basically fine and fun in small amounts but bad for us in large amounts and really bad for us if consumed in the massive regular amounts reserved for nutritive staples. One can only guess at what volume of gin or poundage of Toblerone six hours of Special Treat a day would convert to.”

Although Wallace died in 2008, whereas Ditum is a prolific columnist and commentator at the height of her career, both writers have a lot to say about the internet.

In Toxic, while Ditum is writing about a particular decade—the book serves as a retrospective and a corrective—it’s at its most piercing and luridly gripping when the events she narrates are, implicitly or explicitly, juxtaposed with the norms of 2023.

The way she describes how Britney Spears, Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan and Amy Winehouse were treated by the media is genuinely harrowing—and that’s principally because this period of history (history!) seems so recent to us.

Well, it does to me. And people around my age. And, quite transparently, to Ditum, as well. The book is a masterful feminist polemic and technology plays a key role in understanding the interplay between celebrity, mass media and the general public. She doesn’t let us, or herself, off the hook; we were complicit voyeurs—all of us.

Sure, some people enjoyed and perpetuated the humiliation-as-entertainment that was meted out to these women more than others, but that was a matter of degree rather than a case of “innocent bystander or rabid consumer”.

New technology, Ditum points out, facilitated the disparagement and seedy objectification of its celebrity victims. “Upskirting” was only possible due to the development of lighter and more portable cameras, for example.

But that only explains how the media behaved the way they did, not why. And Ditum has an answer to the latter, too, of course: misogyny (barely) masqueraded as an amalgam of concern and adulation.

“I was sixteen at the start of 1998”, Ditum writes. “In 2013, I turned thirty-two. The years I’ve covered in this book marked my passage from childhood to adulthood, but they also marked the passage of the internet from novelty to utility.”

It’s ten years later now, and I’d probably reformulate and expand that pithy line about “the passage of the internet from novelty to utility”, to gesture towards something darker, more damaging and addictive. (It’s not that Ditum isn’t alert to the inexorable and shifting role that the internet plays in our lives—she quite obviously is—but I’m curious about the best way to characterise how it’s morphed in the last decade, too.)

Of course, the way we use the internet is partly to do with the unabated way it’s now even more accessible and how its features are constantly proliferating, which Ditum details:

“At the start of this period, 30 per cent of the US population had access to the internet. (As late as 2005, gossip blogger Perez Hilton was spending most of his days in a coffee shop because he didn’t have a connection at his home.) By 2013, 71 per cent of the US population was online. In the United Kingdom, the rise was starker still: from 14 per cent to 90 per cent. The increase in time spent online is even more instructive. In 2005, UK users spent an average of ten hours a week on the internet; a decade later, that figure had doubled, and the way people were accessing it had changed, too, with the widespread adoption of smartphones and the rise of social media.”

But this new technology—iPhones, laptops, and crucially, the internet itself—has also done something to us. It’s changed us. Both as individuals and as a culture.

Curious about how other people—both younger and older than myself—thought about the internet, how it has affected their lives, I asked friends and family. And I posed a question on social media. Something to this effect:

“Does anyone ever wish the internet had never been invented? Or maybe that it would turn up in five years’ time from now? I’m 35 and I feel like I’ve missed out on a lot (but also gained plenty of things) from growing up mostly online. I’m interested to hear people’s thoughts. And maybe include how old you are (roughly) as I think that’s relevant too…”

The responses were interesting—both from strangers and people close to me. And there seemed to be a pattern that correlated somewhat with the age of the respondent.

Broadly speaking, younger people—mostly in their twenties—spoke about online culture as generally malignant (albeit useful, too); while older individuals had a more temperate view, tending to highlight its benefits in terms of increased functionality and productivity, while still acknowledging the tribalism and radicalisation that sites such as Twitter, Reddit and even Facebook exacerbate or fail to tackle.

My “experiment” was hardly methodical, and I think it’s safe to say its results are inconclusive. But I do think that what people told me makes a kind of sense, at least intuitively. If you’ve grown up immersed in the online world, you’re bound to regard the internet as an aspect of culture. But if the world wide web arrived about halfway through your life, you’re probably more likely to see at as a tool.

It’s not as simple as that, of course. And I never promised any answers. But it seems to me that if your life has been bifurcated by the arrival of the internet (and when exactly the internet began—and what was merely a dress-rehearsal—is another question I won’t be answering), then you’re probably better placed to use it with some discretion.

And, probably, you are less damaged, in one sense, than the rest of us.

That seems like a dour note to end on. So here’s a reply I received from a guy on Twitter and which I found pretty funny: “Wouldn't have a job without it, that's the only positive thing it did for me…”

This might be oversimplified, but: the internet is great. Social media is not. It's a maxim that works well for me.

I was born in 1975, so I grew to maturity in the pre-internet era. Isn't that slightly marvellous to say? It's as if I remember fin de siècle Vienna.

I first heard of the internet years before I first experienced it. In the mid-90's The Independent ran a regular column about it; essentially explorer's despatches from the esoteric new frontier of the "world wide web". And there was Nightwaves on Radio 3 where more cerebral, rather porentous speculations about the "information superhighway" might be overheard.

The fact is I've never quite become fluent in the internet even though it has deeply impinged on my life. I love to read books, I love to read print. And I find the internet clashes horribly with this, however consistent they are in theory. Reading anything at all online feels relatively superficial. I'm caught by the inexorable, subliminal pressure to skim and move on. I struggle to concentrate. I muse less when reading online. I become discontent and hazy after about half an hour. I need a lot of breaks. And the worst of it is that I read less books now. It's dispiriting for this natural born reader. So yes, I sometimes wish the internet had never been invented.

I want to research the comparative neurology of reading print and reading online. Do they involve the same parts of the brain? Is there a physical basis for my idiosyncratic phenomenological troubles? Or am I just old? I think I've a project for 2024.