Palimpsest: a page or surface that’s been used and re-used; the initial inscription or meaning faded but still partially visible beneath subsequent text or imagery. It’s also the name of a skeletal, keening song by the artist Smog that I loved as a teenager. It’s the name of Gore Vidal’s memoir. And it’s a term my mother uses in her own work.

Heterotopia: I’m somewhat familiar with this term, too – it’s attributed to Foucault, who I know very little about, and means something like “a space that is somehow ‘other’, contradictory, or disruptive.” (If that seems oblique, it’s because it’s meant to be – don’t shoot the messenger.)

I’ve noticed that both of these words crop up in the art of the man I’m on my way to interview.

David Chalmers Alesworth is a friend of my mother’s, but I’ve never met him; and my knowledge of his work is limited to a cursory scan of his Instagram page and a PDF file summarising a recent exhibition of his called Hortus Nocte – The Dark Garden.

I’m nervous. This isn’t my world, and I don’t speak its language. So, it’s these two words – palimpsest and heterotopia – that I keep in mind, ready and poised on my tongue, as I walk along the riverbank from Wapping Wharf towards Spike Island and David’s studio.

We meet at the reception, and he appears distracted – almost surprised to find me – though he messaged me on WhatsApp about twenty minutes ago. We take a lift to the top floor, and I ask how his day’s been. He tells me he’s spent it backing up some important files but that the “fucking hard-drive” he’s just bought has failed him – he may even have lost some work.

The expletive seems incongruent with the diffident character I’ve just met, but it also reassures me. It conveys a casual intimacy. But this lapse – if it is one – doesn’t portend a foul-mouthed interview, nor a particularly intimate one.

I set my phone down on the table in the large, stark room David has led me to, and start by testing the recording app I’ve downloaded for the occasion. He isn’t quite sure how to introduce himself: he’s a gardener, a sculptor, a teacher and an “accidental embroiderer.”

Raised in Surrey, he attended Wimbledon School of Art, won a sought-after fellowship at Kingston, and then went on to teach at Glasgow’s Art School. It was around this time that he met his first wife who “brought him to Pakistan.”

This represents the beginning of a (perhaps) unlikely relationship with a country that is at once very foreign but indelibly linked to Britain; its bloody partition from India – its cauterisation in a sense – less than a century old. He lived in Karachi at first, which he describes as “a mega-city of twenty-two million people, a crazy, interesting place, under seething development… everything being built up and broken down, people living in cardboard boxes alongside luxury villas.”

And then latterly, Lahore: “the city of culture – it’s Kipling, it’s the British Raj, but also Mogul architecture. The sheer “depth of culture” you find in Lahore isn’t so visible in Karachi, he tells me.

He explains his dual identity, gardener-artist: “the garden is interesting in the context of Pakistan because it’s a post-colonial garden, everybody wants a rose garden; they want an English lawn, which is totally inappropriate for a subtropical desert” climate.

“I wanted to collapse my ‘gardening self’ into my ‘art making self’. Alongside teaching, I was running an art career and making gardens throughout Pakistan, from the Arabian Ocean right up to the Chinese border”. To David, “gardens are always palimpsests” – there it is – “because there’s never terra nullius.”

The word “paradise” comes from “pairidaēza” in ancient Persian, a language I later learn is called Avestan. “The garden carpets came out of a proposal… around the time the Louvre was being franchised to Abu Dhabi”, a commercial enterprise he views with disdain. This was evident in his pitch because "they didn’t go for that project… understandably.”

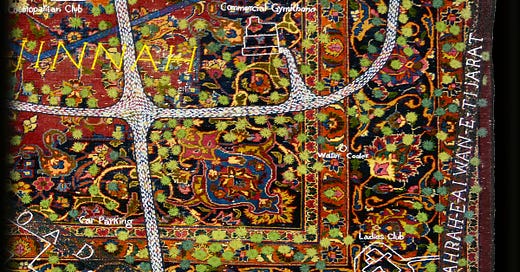

Instead, he “took the idea and moved it laterally onto a Kerman carpet which he had been hauling around for years. Exquisite, but full of holes, wrecked.” These carpets depict charbarghs, Persian walled garden that represent the four paradisiacal gardens in The Quran. Using maps of Western gardens – “Versailles, Hyde Park or Lawrence Gardens in Lahore” – he transposes their designs onto Persian carpets.

While Alesworth doesn’t limit his practice to variegating ancient carpets with layers of exquisite embroidery – evoking historical allusions and metanarratives – it’s these pieces that captivate me most.

They’re straightforwardly beautiful, of course, but also cerebral; they pose questions and can be read as considered provocations; they ask you to think, not simply marvel.

But regarding the medium he works in, he offers an unlikely admission: “I’m not really interested in craft – and I’m not an embroiderer”.

How is he treated in Pakistan, as a white, well-spoken English man? “In Lahore, I’m looked at as a remnant of the British Raj: people come up to me and have conversations about Sherlock Holmes, or afternoon tea – whatever their idea of Englishness is.” This fascinates me: the idea of English culture preserved in aspic. Perceptions unchanged for a century. But rather than finding these interactions irritating, he decided to lean into this identity – “to embrace it.”

David holds dual Pakistani and British citizenship, is married to Huma Mulji (also a celebrated artist), and speaks Urdu quite well. But his mother-in-law doesn’t trust him to drive in Pakistan and insists on a chauffeur. As he tells me about this, it sounds charming – almost quaint – but not all his interactions have been so innocuous.

He’s experienced the Pakistani military’s extreme paranoia: his home invaded in the middle of the night. Shortly after our meeting, he elaborates in an email: “one of the reasons we left Pakistan was a misunderstanding with military intelligence. As a foreigner, I was always somewhat suspect.

“One day after putting reflective stickers on electric poles on our street to prevent collisions, I was arrested by the military intelligence who thought I was marking one of their assets.

“Although they subsequently let me go, they continued to probe into my life – through calls to my employers, by sending groups of armed soldiers into our home to question me at odd hours and without notice.”

As I leave Spike Island and David stays behind to sort out his “fucking hard drive”, I feel enriched but like I’ve just attended a lecture, rather than had a conversation. Gardener-artist is an appropriate designation for him; but I feel like I met the teacher rather than the artist or the gardener – and, to me, that’s no bad thing at all.

https://davidalesworth.com/

https://www.instagram.com/alesworth/

https://www.spikeisland.org.uk/our-community/studio-artists/david-alesworth/